There was a flying ace, a fighter pilot who left Arkansas County to travel the world—Frank Tinker. He was a real-life war hero, a buddy of Dad’s. He used to buzz us out in the fields, zooming loud and low over the farm in his single engine Jenny, laughing. We heard he met a sad fate in a Little Rock hotel—shot and killed over a jealous woman. He was buried in DeWitt with “¿Quien Sabe?” (“Who knows?”) engraved on his tombstone. Folks tended to shy away from scandal, so his name went unspoken.

There was also in St. Charles during this time a villain whose name was on everyone’s lips. From the church sanctuary to the docks, tales of his villainy spread until an image formed in my mind like some graven idol of the Old Testament. He was known as “The Colonel,” said to be rich as Midas and mean as Herod.

LC snickered when I asked which war he fought in. “The Colonel? He got his medals off a Memphis pawnbroker.” LC explained how the old man lived alone ever since his invalid wife up and died of sheer spite; he kept a house in town and a plantation toward Skunk Holler. Over the years so many housekeepers quit on him, he took to writing checks to the Pea Farm, paying large sums to parole poor gals out of prison—and straight into bondage.

“The Colonel rides his tenants hard,” LC said. “Works ‘em ragged. Awhile back, he drilled a well to irrigate his land. Now he charges the small farmers cash on the barrelhead for water.”

I stalked the springtime streets of St. Charles with a sharp eye out for the Colonel, the only dark blot on April. Roaming the soft green woods, my brain set to reeling from misty breezes. At school I daydreamed and at home I turned bitter and sulled up, snapping at Dad. On top of all this, Mudcat was fixing to have her first litter of kittens. What if she were too small? I seethed with indignation.

“You’ve got spring fever,” Dad concluded. He pronounced the cure: a spell of fishing with Uncle Harold. He said I could come home after Mudcat had her kittens—“Harold’s the dang zookeeper, so let him deal. Cool your heels on the River—it’ll do you good.”

But I didn’t want anything to do me good. The heathen in me reared up. First chance I got I snuck away from Uncle Harold’s, scaled the fence back of the Colonel’s townhouse and stole peaches off his trees. Emboldened, I returned with a rock the following night and broke his basement window. LC confronted me after school: “Are you gonna tell me what’s going on, or do I have to throw you?” I bowed up on him, but as he was still a head taller than me, I thought better and dropped my fists.

“You’re the one took out the Colonel’s winder, ain’t ya?” he said. “I best keep you in my sight, Cole Younger!”

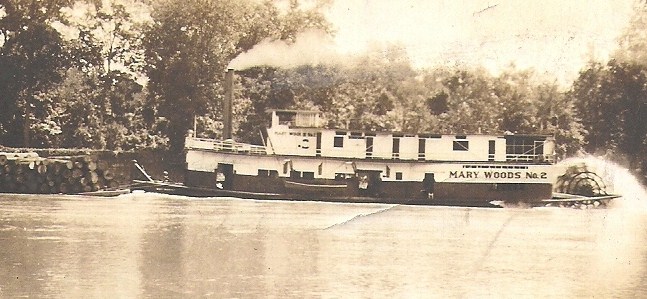

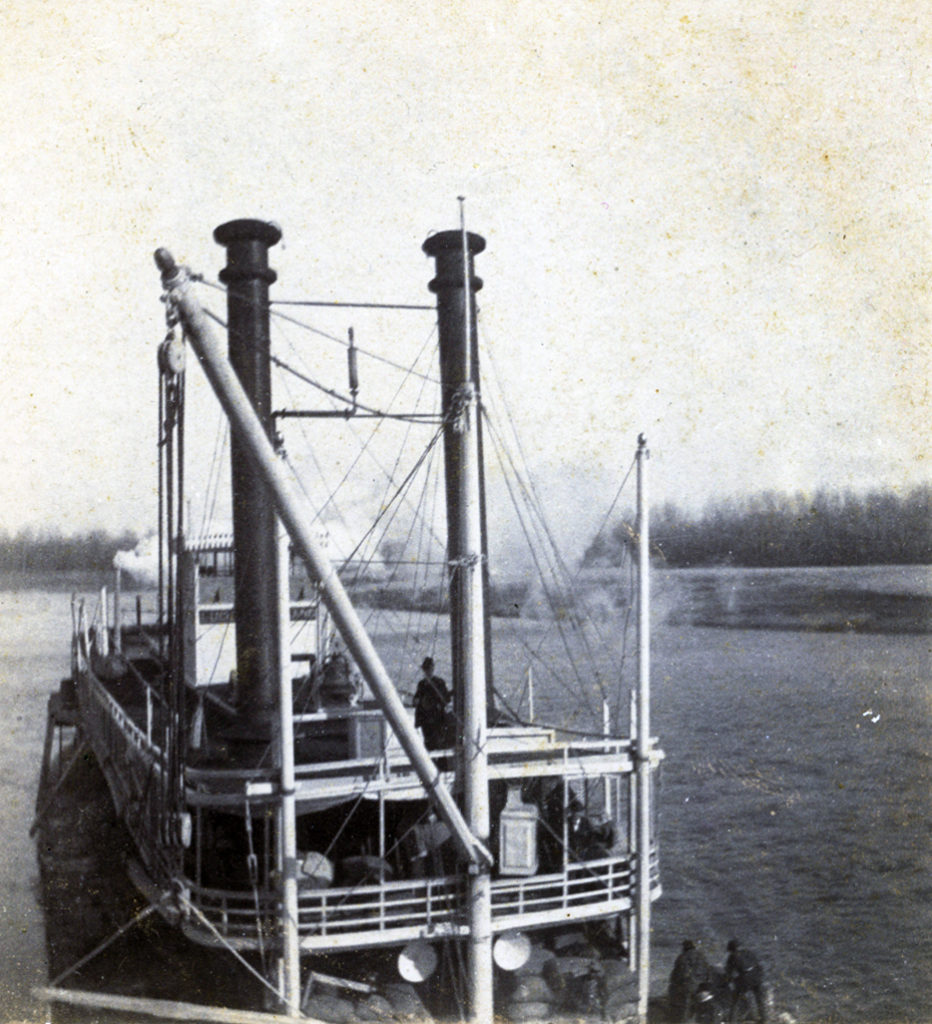

We came upon John standing by the log chute at River Bend. The Mary Woods churned our way, red paddlewheel shining in the distance. She was coming to pick up a tow—a bunch of floating logs all chained together. It was fun to watch the giant tree trunks plunge down the chute into the River, sending spray sky-high. Cypress logs were already piled at the head of the chute and a team of draft horses appeared, shiny with sweat, pulling a load of hickory. Mr. Williams walked alongside.

“Hey Mr. Williams,” called LC. “How’s the molasses business?”

“Like they say—sweet,” he replied. I realized Mr. Williams was a woodsman by trade and as he talked timber with LC and John, up strode the company man.

“Get that hickory down the chute, boy!” barked the foreman. At the sound of a Yankee accent, the four of us turned to study the foreman’s pink face, not saying a word. “We got to chain the hickory to the cypress first,” began Mr. Williams, but the foreman interrupted with an ugly oath. Mr. Williams shrugged and walked back to the wagon team.

“You see that?” John asked LC, who nodded. “What happened?” I said. “Watch,” they muttered.

The men used iron pikes to move the bare hickory trunks, straining and grunting. As the logs thundered down the chute, splashing into deep water, I waited for them to shoot back up like big corks. But nothing happened—the logs just sank. John and LC hooted with laughter as the Yankee threw his hat to the ground, cussing.

“I done told you we had to hook ‘em to cypress to float ‘em,” Mr. Williams sang out as LC and John doubled over, laughing until tears ran down their cheeks. Hickory, being a dense and heavy grain, doesn’t float easily. The day’s work was lost. The foreman caught my eye. “Damn River Rats,” he snarled, so I snatched up a hickory nut and beaned him on the temple. “Run!” yelled John and the three of us hotfooted it all the way to Uncle Harold’s houseboat. “You looked like David and Goliath back yonder,” gasped LC.

Somehow my Uncle knew all about the broken window. “Brent’s feeling his oats, all right,” he sighed. “Have y’all been to see Mother Carey? She cleared up my plantar’s wart–had me bind a slice of potato to the sole of my foot–worked like a charm.” At this, my companions grabbed ahold of my arms and ordered me to march. We left Uncle Harold standing by the stage plank, chuckling, and turned past the cold spring, following the River. After much pleading on my part they finally let go. “Who the Hell is Mother Carey?” I demanded, to no avail. “You got some tobacco?” LC asked and John nodded. “What’s going ON?” I hollered.

The path ended in a clearing with a flight of stone steps leading to the water, where a houseboat floated atop cypress logs. Its pitched roof was like a lean-to, and in the doorway stood a little old woman. The minute her glittering dark eyes fell on me I got a rigor—a shiver that rippled from head to toe. The old lady lifted her pipe. “What’s a matter there?” she cackled. “A rabbit run over your grave?”

John solemnly handed his tobacco pouch to Mother Carey and we went inside. She rocked slowly in a wicker chair as we sat cross-legged on the floor and my case was presented: “He’s moonstruck bad—he’s off his feed.” In the dim light I could see the walls were papered in newsprint. Bundles of sweet-smelling herbs dangled from the rafters. When she turned and asked, “What’s your question?” I blurted out the first thing that popped into my head.

“Why’s the Colonel alive and my Momma’s dead?” For answer, Mother Carey lit her pipe. The smoke drifted toward the three of us, and things shifted somehow. It was like we sort of sank into the floor—I can’t explain. “Don’t you worry about the Colonel,” her raspy voice echoed overhead. “Y’all be dancing on his grave before the next full moon. And don’t worry about your momma either—you gots her eyes.” The voice fell silent. As soon as we could lift our heads, we crawled out the door on hands and knees. The sunshine revived us and we stumbled back to Harold’s place lost in wonderment.

A week went by and nothing happened except that Mudcat had three kittens. I cheered up some; Bo was happiest of all, as though he was their dad. The Dupslaff kids wanted the two calico ones, but I secretly hoped we could keep the third kitten, a gray tabby. I was walking to LC’s house, musing about the kittens, when I noticed someone galloping up the road—The Colonel! Before I could look around for a good rock to chunk, he passed by in a cloud of dust, flogging his bay mare like a madman. It made me so angry I ran home to the houseboat, not wanting to see anybody, not even LC.

“It’s good you got here when you did,” Uncle Harold said. The weather had turned. We herded the animals inside minutes before a cloudburst ushered in days of rain. The houseboat rose in the water like an Ark as the two of us holed up, playing cards and petting cats. After the rain stopped, we didn’t see Dad for a couple more days and I fretted—but as soon as the floods receded, he came bringing news: the Colonel was dead.

“Word is he was checking fences at the plantation when the rain spooked his horse,” said Dad. “The horse took off into the swamp. Rolled over on him—they say he drowned and got crushed, too.” Uncle Harold observed that “if anybody deserved to die twice’t, it were the Colonel.”

I was glad to get back to our farm, but I still had something to do. I set out for the Saint Charles cemetery, resolved to dance on the Colonel’s grave. To my surprise, there was a family gathered around the big white marble monument (the Colonel had special ordered it from Little Rock years before). One of the people turned—it was Mattie Lively, my old schoolmate from Skunk Holler. I barely recognized her, she was grown so tall. She smiled and said, “Why, Brent Granberry!”

Turns out, the Colonel’s name was Harvey Walburton Lively—Mattie’s grandfather. He’d quarreled with his only son, banishing him years ago. But since nobody could find a will, the inheritance fell to Mattie’s dad. The farm was to be leased out and Mattie was coming to live in the townhouse. I offered to fix a certain window and as we talked, the old bitterness inside melted clean away. “I missed you, Mattie,” I said, and it was true. “Hey—want a kitten?”

Things shifted after that, in a good way. Cured of spring fever, I looked forward to the sun coming up. LC and I laughed at how folks in Arkansas County said the Colonel’s grave was the most fertile plot in the Saint Charles cemetery. Tall white iris grew thick as weeds against his marble marker, adorned year-round with yellow stains.