Autumn on the River is busy season. There’s the Reunion at the end of October, but before that comes the sorghum harvest and molasses-making. I was itching to see my first molasses-cooking party—LC said it lasts for days, with music and circle dances and a big spread. School lets out early, perking folks up.

Dad liked to broke his back cutting the 10-foot stalks, topped with tassels that have to be sawn off by hand. From sunup to sundown we piled green cane onto the hay wagon, falling asleep as soon as supper was over. My hands blistered and I got behind on the dishwashing—when we ran out of clean pots and pans Dad kept going. He switched to the Dutch oven and built a fire out in the yard.

One evening we were tucking in to a mess of stew when LC and Wolf showed up. After dinner, we lounged on the porch. The moon shone through the pines as LC cleared his throat. “Mr. Granberry, can Brent ride with us to the molasses-makin’? We got room in our buckboard and he can camp with John and me.” I watched Dad, holding my breath. He grinned. “That’ll work. I’ll be in Uncle Harold’s tent. Just follow the snoring.”

The next few days were a blur. Between the nip in the air and the colors in the leaves, I went around dazzled, daydreaming. LC talked about molasses nonstop; he was sharpening his sweet tooth. “The best barbecue sauce has sorghum in it. The pit’s already dug at the Williams’ place—they’re probably scalding the hog now. Cracklings are my favorite,” he rambled as we walked home from school. John was already gone ahead up the River. “He’s pitching camp by the River, away from the big house,” LC said, “since Wolf is coming to guard the camp.”

“Guard it from what?” I asked. LC didn’t answer until we came to the fork in the road. As he and Wolf turned off for home, he hollered, “Ghosts, that’s what! Guard it from ghosts!” I stared until they were out of sight and a dust devil sprang up in the empty dirt. My scalp prickled and I ran the rest of the way home.

That night I lay awake, listening for Dad’s snore—the house was too quiet. “Dad? Is the Williams place haunted? LC says its haunted.” The Williams homestead, for years the site of the molasses-making, had fields and orchards and a big stone wishing well. Two maiden aunts and their elderly brother lived in the farmhouse in peace and quiet, except for the yearly wingding. LC called it “sorghum philanthropy.”

“He’s just rattlin’ your cage, son—go to sleep.” It’s true, LC held to uncertain lore, as when he swore if a Model A were parked with the engine running, the tires would melt. He’d cross his heart while describing in detail a hoop snake, gulley cat or snipe. LC got me to believe knotholes on trees were doors to beehives—for months I knocked on every knothole I saw. Maybe ghosts are uncertain lore.

When school let out we ran yelling down the steps. At the Brown’s we climbed into the loaded buckboard, like a big shoebox on wheels, with Mr. and Mrs. Brown up front guiding the draft horses. LC’s older brother Henry followed on horseback and Wolf stalked beside. Being in high spirits, we took turns singing—that is, the Browns sang “This Old White Mule of Mine,” followed by a round:

“I’m going to leave ol’ Texas now, they’ve got no use for the longhorn cow

They’ve plowed and fenced my cattle range, and the people there are all so strange…”

More wagons entered the road, winding past hedgerows of purple sumac and goldenrod. Mrs. Brown began “Auld Lang Syne,” and a lump came into my throat—Momma used to sing that. On reflex, I looked to the heavens that were bluer than a bird egg and it was like a vision dropped from the sky, as if Momma whispered in my ear: Remember, Poppy River makes molasses candy, the best molasses candy in Arkansas County. The River Sisters—surely they’d be there! I resolved to scour the Williams place for any sign of them.

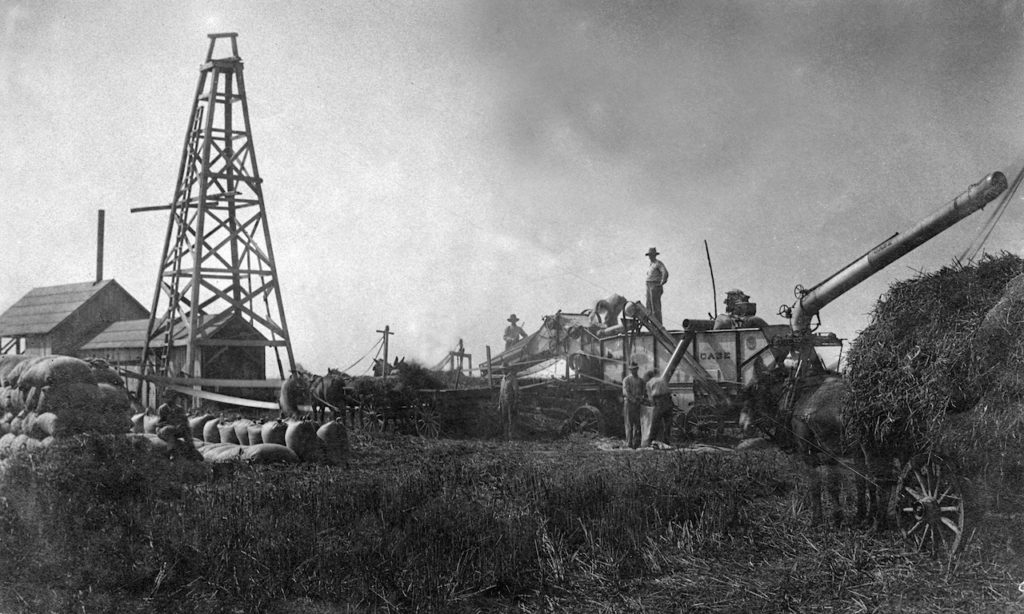

The wagon topped a rise and the air hummed with sudden laughter and conversation, jangling harnesses, rumbling engines. Distant smoke spiraled from the boiling molasses as folks gathered in oak and pecan groves, unfolding card tables and tents. A group of men were setting up a stage next to the muscadine arbor and kids played crack-the-whip, snaking in a blur until the whip snapped, sending the small ones rolling in the grass. LC pointed to where a mule trod a circle, hitched to a long pole turning the grindstone. “First we try the raw cane juice,” he said. “But just a sip—you don’t want to spend the weekend in the outhouse.”

Escaping the wagon, we passed some folks working an apple press and a girl held out a cup. “Want some live-apple juice? Say—is that a timber wolf?” With a nod to the girl, LC grabbed my arm and steered toward the settling vat. “First things first,” he repeated. LC was right—a little of that foamy, sappy juice was plenty—it tasted sharp as the color green. We took off toward the river.

John’s shell boat was tied to the bank and the camp looked a sight. A raggedy flag (red silk bloomers, according to LC) flapped atop the tent pole and from trees hung all manner of gear: spyglass, drinking gourd, railroad lantern. A circle of stones marked the fire pit, next to which John lay with his hat over his eyes. LC whispered to Wolf, who broke into a piercing howl. Scrambling to his feet, John cussed us for being late. I stared off through the trees while he argued with LC about whether to play horseshoes or go find the musicians. “You’re mighty quiet,” said LC. “What’s eating you?”

I announced my mission: to find three sisters, name of River. Apparently, the girls were as legendary in St. Charles as in Skunk Holler—LC and John gawked as though I’d sprouted a second head. “The River Sisters ain’t been seen in a good while,” LC began, but John shouted him down, betting us a nickel they were close by right this minute. After more arguing, we agreed to fan out on a search and meet up in an hour. “Wolf, stand guard,” LC called.

I plunged into the crowd and caught up to a buffet line, asking every few paces if anybody had seen the River Sisters. People seemed startled, but in the next breath they’d be talking a streak—everybody had a story about the River Sisters. Begging pardon, I excused myself and ran to the nearest card table, asking some poker players if they’d seen the River Sisters. That was the end of their hand, as each fellow folded his cards and talked over the other, vying to praise the girls. I gave up on the poker players and hurried to find the musicians.

The boys were tuning their guitars behind a shed, passing a jug. “Have y’all seen the River Sisters?” I panted. “Speak up, kid—don’t be a mush-mouth,” said the washboard player. When I repeated the question, they welcomed me warmly. “Sit down—have a nip of this blueberry wine.” Dad gave me some blueberry wine once when I had the croup, so I took a swig. The warming potion spread like electricity down my middle as the musicians debated over which songs to play for the River Sisters, ignoring my presence. This wasn’t working as planned, so I went in search of LC.

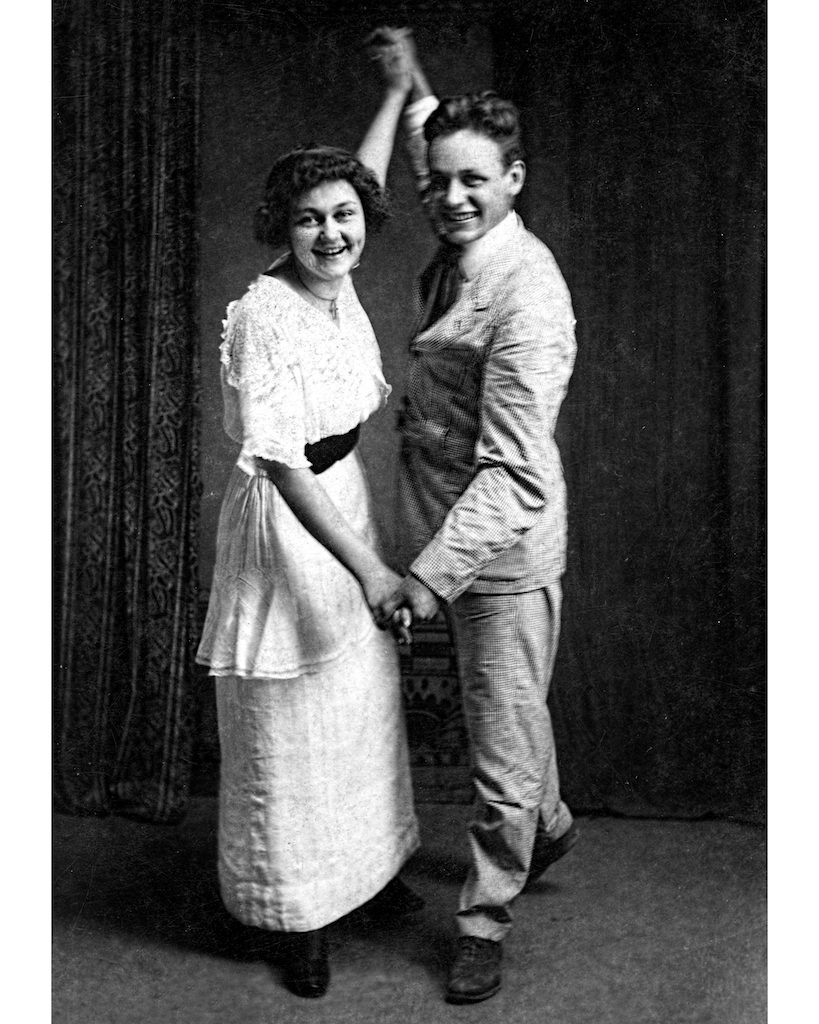

I found him at the Flying Jenny, a sort of giant seesaw for brave people. “They’re here all right,” LC said excitedly as John pushed through the multitude, hollering, “They’re here!” We spotted a table by the barbecue pit and compared notes over messy helpings of barbecue. It was like I thought: nobody had seen the River Sisters, but everybody was sure they were here. “Wonder who started that rumor?” LC hooted. Bonfires flared in the distance as the musicians took the stage, dedicating the song to “the sweetest gals in Arkansas, the River Sisters.” The Cajun reel went round and round: “When we didn’t have no crawfish, we didn’t eat no crawfish,” as couples danced under a full moon.

The rest of the weekend flew by. I won a penny jacknife pitching horseshoes, and Dad and Uncle Harold jarred up 30 crates of fine amber syrup—enough to pay bills. Back home, I slept like a log. But Dad woke me before dawn. “I want to fetch a premium price for our first batch—what do you think?” he said, raising the lantern. Mason jars of sorghum molasses covered the kitchen floor, table and counter. They all bore brown paper labels: “Granberry’s Hainted Molasses.” Dad had stayed up all night making the labels and I didn’t have the heart to tell him he misspelled “haunted.” Turns out, it didn’t even matter—folks bought it in droves, said it was the best they’d had, and we were in tall cotton for a good while.