The summer after the River Sisters went away, I got sent down to St. Charles to stay with my great-uncle. My mother was expecting; she had the morning sickness so bad it was decided I would spend summer vacation on Uncle Harold’s houseboat.

I could hardly wait to get a hook in the water, and when daddy dropped me off, it felt like coming home. Nothing had changed since my last visit years before: Uncle Harold was just as skinny and bent, with wrinkly brown skin like deer leather. The White River was still green and endless, carrying the smell of a million growing things. Uncle Harold’s houseboat smelled like wet dog, pipe tobacco and fried fish, which we ate a lot. In other words, it was heaven.

I played with the Dupslaff kids down the way, a German family that treated me like a dark-haired version of one of their gangly towheaded boys and girls. Miz Dupslaff made the best bread pudding with whiskey sauce; between that and Altha Ray’s fruit pies, I was eating better than at home, where sweets were for special occasions.

Altha Ray was Uncle Harold’s lady friend. She came by every few days to tidy up the place and fix a big lunch. She and Uncle Harold liked to sit in rocking chairs on the deck, staring off at the sunset. Uncle Harold’s other friend, Mr. S.E., came over Sunday afternoons to play cards and “have a nip.”

Uncle Harold had a nip most every evening. He often fell asleep in his big easy chair in the living room. My room was a little space behind the kitchen, with just a cot and a bookshelf, but cozy. Bo, Uncle Harold’s lab mix, slept with me, something momma never would have allowed.

We went to St. Charles once a week, to the Mercantile. It was a relief to learn Uncle Harold wouldn’t be taking me to church—he said Sunday school for him was fishing with Mr. S.E., outside under the sky. And since “S.E.” stood for “St. Elmo,” I figured they must have a line on the hereafter.

Every time Uncle Harold went to pay at the Mercantile, whether for salt, sugar and flour or penny nails and lye soap, he pulled out a leather pouch, reached inside and handed something to Mr. Ballard. It dawned on me that Uncle Harold was paying for his groceries with pearls! Freshwater pearls from White River mussels.

I began snooping to see where he kept his pearls, and sure enough, one afternoon I peeked through the window as he was lifting up his mattress. He took out a small wooden box and opened it—it was chock full of pearls. So, next time Uncle Harold had a nip and fell asleep in the chair, I went and snuck one little pearl. I wasn’t greedy; I only wanted one teeny-tiny pearl.

When I showed it to the Dupslaff kids the next day, they did not seem impressed. The eldest went and rummaged inside their houseboat and came back holding a matchbox. Inside was a pair of long, skinny pearls. “These are slabs,” the boy said. “River tears,” explained a sister. “Two river tears pulled from the same shell’s bad luck.”

Uncle Harold asked me to run get a newspaper in town, so I hopped on the bicycle and took off, forgetting I still had the pearl in my pocket. On the way back I came to a one-lane bridge and saw a big dry-lander boy standing blocking the way. The Dupslaff kids had warned me about this bully. They called him “The Troll” because of his frown, and he was glaring at me now.

“Toll bridge,” he yelled. “Empty your pockets!” When I hesitated he rushed over, knocking me off the bike. I reached in my pocket and slowly handed him the forgotten pearl. “I bet there’s more where this came from!” crowed the Troll. I took off running through the woods, clutching tightly to Uncle Harold’s newspaper.

After doubling back a bunch of times and crawling through the swamp, I thought I had lost The Troll. I finally got home and handed Uncle Harold the tattered newspaper, along with some story about getting chased by a swarm of hornets and leaving the bike in the woods. He gave me a funny look and said I could get the bike in the morning. I went to bed praying The Troll would leave us be.

That night, Bo woke us up barking. Footsteps sounded outside on the stage plank as I ran to the living room. “Uncle Harold!” I yelled, “It’s The Troll—he’s coming for your pearls!” In an instant, my Uncle grabbed his shotgun and was out the door. There was a single shot followed by unearthly howling.

“This no-good’s gone and cursed my pearls!” my Uncle thundered as I stepped outside to see The Troll writhing on deck, his hand full of rock salt. “The only way to take off the curse is to throw that box of pearls into the Everlasting Pit!” Uncle Harold ducked inside and retrieved the box. Handing it to me, he dropped his voice as the bully thrashed and moaned.

“Take these—stay gone til this blows over, and then sneak back here,” he said. “That way we don’t have to worry your parents with this mess.” I began to wail. I didn’t want to throw away my Uncle’s treasure.

Uncle Harold leaned in so close his whiskery whiskey-breath tickled my ear. “You think these the only pearls I got hid away? Listen: I was a mussel-sheller for 40 years. I got little cedar boxes like this one buried at every cold spring in Arkansas County. I got pearls to last til the Resurrection.”

“But where do I go?” I cried as he stuffed the box inside my shirt and threw his jacket over my shoulders. “You just head up the road and catch the first bus comes your way,” he said. “Don’t be scared–there’s a full moon to see by. Just go til you git where you’re going!” With that, Uncle Harold gave me such a shove that I staggered off into the night.

I was asleep on the bench outside the St. Charles post office when the sound of voices woke me. The sun was up and a big green school bus was parked at the stop, surrounded by a bunch of kids. The box was still tucked inside my undershirt. I fell in line with the gaggle of kids and got a few curious stares as I took a seat in the back.

“Are you with the CCC Floating Camp?” asked a bespectacled boy who plunked down next to me. “I never seen you before.” When I didn’t say anything, the kid started talking a mile a minute about the “Big Dam.” At first I thought he was cussing. But after a few miles of listening to him yack, I gathered we were on a field trip to see a dam getting built up north. The bus was full of kids of Civilian Conservation Corps workers—they all lived in a big string of houseboats near St. Charles.

“Of course, they ain’t finished building the dam yet,” the kid said. “Right now it’s just a big ol’ pit. My dad says it’ll be years before it fills up with water.” I stared out the window. The everlasting pit. A dam upstream from Uncle Harold—what would he say to that? The bus stopped for lunch and the boy, whose name was Nelson, shared his food with me. By now he figured I was a mute, and had quit asking questions.

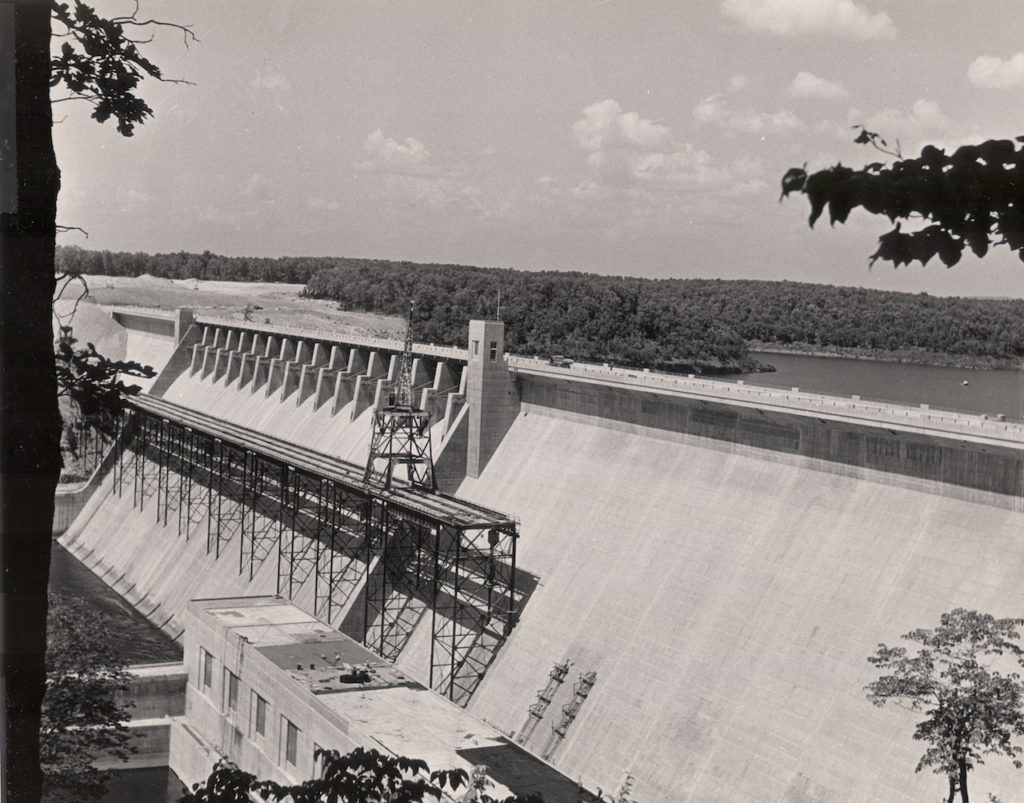

It was late afternoon when we got to the construction site. Bull Shoals Dam. From the road it looked like a mass of scaffolding, planks and catwalks. The grown-ups herded us to a hillside park with a vantage. A CCC man in khakis and a rounded hat started lecturing about the dam. It was going to be as big as an Egyptian pyramid. I spied the nearest overlook—there was an iron railing off to the side. Hugging the cedar box, I bolted.

The CCC man grabbed my collar just as I threw the box over the rail. He shook me til my head rattled, cussing the whole time, but I saw the little wooden box sail into the air and pop open, spilling its precious cargo into the gorge.

The CCC man was hollering, “Does anyone know this kid?” when Nelson piped up. “He’s my cousin, Mister. He’s deaf and dumb. Please don’t hurt him.” It was an impressive job—Nelson’s chin trembled as he fumbled with his glasses and wiped at his eyes. The man shrugged and let me go.

When we got back to St. Charles, I was glad to find Uncle Harold had fixed everything. Before long, everybody in town was talking about how The Troll was stealing Altha Ray’s peaches and she fired rock salt at him. Consensus was he’d gotten what he deserved. Everything went back to usual: I swam every day, S.E. came to fish and play cards, and Altha Ray baked pies for us. Uncle Harold said I did a good thing, throwing those pearls into the pit at the dam site. He never mentioned it again.

But later, after I went home and school started up again, I dreamed about that dam. In the dream, the giant gray concrete wall was finished. Behind it, a deep dark lake was filled to the brim. But at the base of the dam, little pinholes were forming, tiny holes the size of seed pearls, that bubbled and spread as I watched until the whole dam was pocked and crumbling. The giant thing exploded into chunks of tumbling cement as water foamed and roared into the gorge.

I had that dream for years, long after the dam was built and the downstream water temperature dropped, killing off the White River mussels and their hidden pearls. But I take comfort at the thought of Uncle Harold’s cedar boxes, buried beside every cold spring in Arkansas County.

Copyright 2016 by Denise White Parkinson