What is it about sixth grade that it’s the worst year of your life? I pondered this question throughout the long, dreary winter. Skunk Holler was cold and drab, and school was a hard road all of a sudden. The newborn infant said to be my brother (I figured it for a changeling) took up everybody’s time.

Momma stayed sickly after it was born. I couldn’t stand to hear the baby’s colicky cry; made my skin crawl. The day I came home with a report card full of D’s, Daddy said he’d had enough. He was taking me down to St. Charles for a second chance at sixth grade. Any other time, I would have killed to stay on Uncle Harold’s houseboat, but change school? I broke out in hives fretting about it. Momma slathered me with some nasty goo that didn’t even stop the itch. Maybe she was trying to run me off; her strategy worked, as I became too miserable not to leave.

When Dad pulled up to the riverbank, I didn’t look around. Seemed like tears that had been in my eyes for months were still stuck there. Gathering my gear, I went straight to my old room while Dad and Uncle Harold talked. When Dad left, I hardly said goodbye. After tossing around in my cot sniffling, I got up, curious as to why the place was so quiet. A note on the kitchen table said: “Gone to St. Charles. Back shortly.” Next to the note was Altha Ray’s cake tin. Inside was her specialty: chess cake. It tasted so good I began to cry.

Uncle Harold came home with the makings of a party—“just the two of us.” He presented me with a harmonica, and after dinner showed me some tricks on it. At bedtime I found a little wooden whistle on my pillow and brought it to Uncle Harold. He was smoking his pipe in the deck chair, watching the bats swoop. “That’s for you,” he grunted. “It’s a quill I carved out of cedar. Put it on a string and wear it so’s you can whistle for help if you ever get in a pinch.”

I thanked him and went back to bed, stashing the quill under my pillow, and slept a dreamless sleep.

That first day walking to school, the Dupslaff kids fell in beside me, laughing and joking like old times. The teacher at the one-room schoolhouse seemed a nice old lady. When school let out, I wandered off by myself, distracted by Spring. The dirt road came to an end at a grassy entrance bounded by pillars—the St. Charles Cemetery. Rows of skinny gray headstones decked with spirea and redbud stretched into the distance. Some of the graves were decorated with mussel shells. As I stared, a voice called, “Can you see me?”

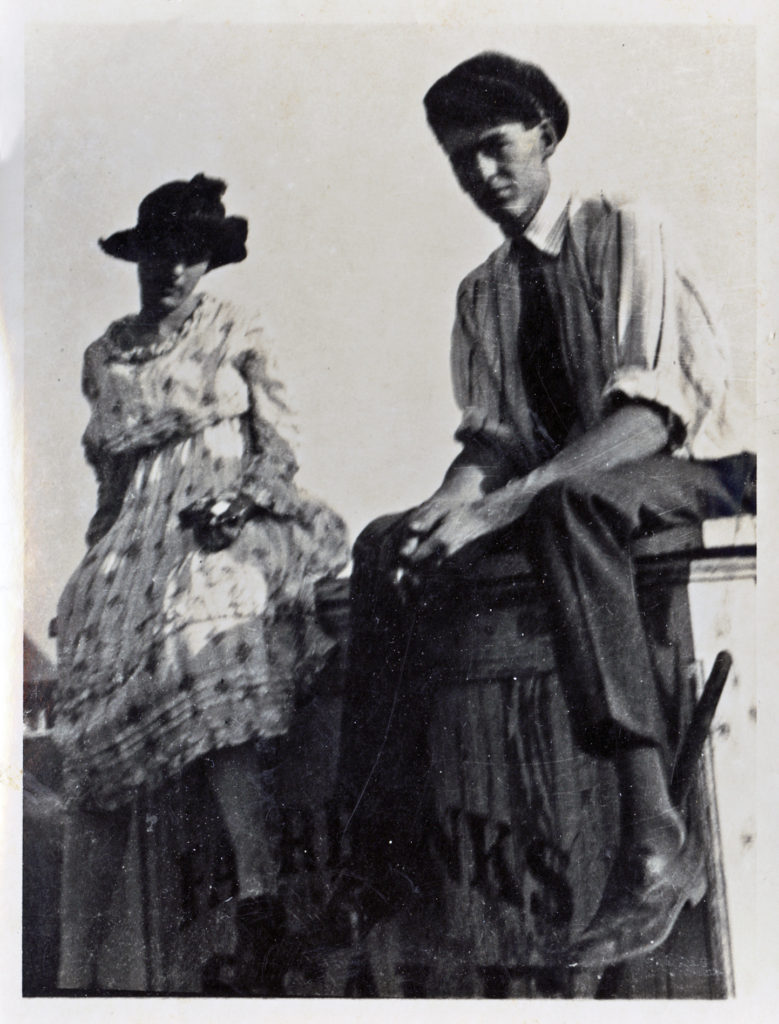

I jumped. Was one of the Dupslaff girls yanking my chain? “Yoo-hoo,” came the voice. “Catch me if you dare!” I darted between the rows, zigzagging toward the back of the graveyard. Whoever she was, she was quick. A wall of thick wild blackberries blocked the way and something whizzed by my nose—a hickory nut! Then one bounced hard off my head. “Hey!” I yelled. “Is this any way to treat a stranger?” The hail of nuts stopped, and a girl stepped out from behind a nearby cedar tree.

Her dress was the yellow of jonquils; her hair and skin and eyes were dark as my own. For such a petite thing she was a crack shot with a nut. We studied each other, and she asked, “What’s your quill sound like?” I reached up to where the string necklace was tucked inside my shirt. I hadn’t even thought to try it out yet.

Setting down my books and lunch pail, I fished out the whistle and gave it a blast. The shrill sound made us both jump. “Hush!” she hissed. “You want to wake the dead?” Giving my hand a quick shake, she said, “Pleased to meet you, stranger. My name’s Helen Spence.” I mumbled something about getting back to the houseboat, and she nodded. “Our houseboat’s near to your Uncle’s. He’s friends with my daddy, Cicero. There’s a storm coming, so I’ll see you tomorrow.”

I picked up my things and turned to find her gone. It was late when I got home and Uncle Harold gave me a funny look when I asked if there was a storm coming. I went to bed without mentioning the girl and her dad.

Next day at school I got blamed for something I didn’t do. One of the big kids in the back row found a flying squirrel on the way to school and hid it in his lunch pail. When the teacher was up front writing on the chalkboard, the kid tossed that flying squirrel into the rafters. Everyone watched it swoop around, closer and closer to the teacher’s piled-up gray hair (she was a Pentecostal). When that squirrel landed on her braid there was pandemonium. After the screaming died down, the bully pinned it all on me.

Despite and because of the pleadings of the Dupslaff kids (“Everyone knows River Rats stick together,” the bully insisted) I was doomed. The teacher whupped me in front of the whole class. Some nice old lady—she swung like a ballplayer!

When the bell rang, I ran straight to the cemetery, but Helen was nowhere to be found. Sprawling in dense moss under a shade tree, I fell asleep. I always sleep hard after a whupping, and this was no catnap—I woke with a start to find it was dusk already. What would Uncle Harold say?

“Your Uncle sent me to fetch you home,” Helen’s musical voice called from the shadows. I grabbed my books and followed as night came on. Helen moved swiftly, surefooted along the paths. She didn’t say a word until we got to the cold spring, gurgling in the dark. “Our place is half a mile up from here. Now, run home—there’s a storm coming,” and she vanished.

Uncle Harold’s houseboat shone like a beacon through the trees, lights in every window. When I came in, all I could do was run up and hug him. We talked about my bad day over second helpings of sausage, grits and a pot of strong coffee. “Your first school whupping deserves your first nip,” observed Uncle Harold, reaching for his flask. Pouring a splash into my cup, he winked. “Today was probably the most fun that teacher-lady had since Prohibition.”

In the morning, I begged not to go to school, but Uncle Harold deemed it necessary for my self respect. I sullenly avoided everybody, even the Dupslaffs. At 3 o’clock I bolted from the schoolhouse and found Helen standing just inside the entrance to the cemetery. “Can’t catch me!” she taunted, and the chase was on.

We ran laughing among the headstones, tagging each other “it.” I collapsed on a patch of clover, panting hard. “Calf rope! I give!” Helen sat down, primly arranging her skirt. She wore stockings like my Aunt Eula used to wear: white cotton fishnet. After I caught my breath (Helen wasn’t even winded) she put her finger to her lips and gave a shush. Slowly she pulled the hem of her dress over her knee. Tucked behind the mesh of stocking was a roll of one hundred dollar bills—biggest wad of cash I ever saw. “That’s $300,” she said, “Daddy needed a place to hide his money.” As I gaped like a mooncalf, she jumped up and ran off, her laughter fading in the distance.

I got home before sunset to find Uncle Harold by the stage plank, scanning the sky. “You been talking about a storm,” he said. Dark blue clouds boiled in the distance, coming in fast from the west. After checking the tow ropes, we moved deck chairs inside. As we sat down to supper, a mighty thunderclap shook the air and the rain came down.

“Do you think Helen and Cicero will be all right in this storm?” I asked Uncle Harold, and a funny thing happened. His head jerked like somebody struck him across the face. Pushing back from the table, he strode to the door and opened it a crack. Flashes of light, roaring wind and rain burst in. “Time for bed,” he said, shutting the door.

A thunderclap woke me from a dead sleep and I was instantly wide awake. I pulled on a pair of rain boots and a slicker. Uncle Harold’s snoring was loud as the storm. Grabbing a lantern, I lit it and made my way out of the houseboat. I had to know if Helen was all right.

I slipped, barking my shin on the rain-slick stage plank. The footpath was easier going, though the trees were thrashing like crazy. I made it past the cold spring but saw no sign of a houseboat. “Helen!” I screamed. The rain ceased and the gale dropped to a whisper; I could hear the clicking of cottonwood leaves. With the force of the sun, a bright light exploded overhead. There was a cracking sound — I turned to see an oak split in two.

Branches crashed down, knocking me to the ground, and the lantern flew off into the dark. Reaching for the quill, I blew as hard as I could, over and over, whistling til all my air was gone. I must have fainted, because when my eyes opened I was in Uncle Harold’s easy chair, bundled in a horse blanket. Bo was licking my hand, wagging, and the storm was subsiding. My Uncle brewed coffee as I checked for injuries—just a barked shin. “How’d I get here?” I asked.

“I found you on the doorstep. Do you believe in miracles?” Uncle Harold held out a yellowed newspaper clipping with the headline: “Outlaw Shot After Escape.” He shook his head, muttering, “They called her the Swamp Angel, but she was just a little river girl.”

The article was ugly as it was short: “Helen Spence, the houseboat girl who killed the man on trial for killing her father, Cicero Spence, was shot down after her fifth escape from Arkansas Women’s Prison. The Grand Jury is investigating claims Spence was the victim of a plot by corrupt prison officials. Spence was buried today beside her father in St. Charles Cemetery’s potter’s field.” I put down the paper. There was no Spence houseboat by the cold spring, not for years and years, anyway.

A telegram arrived in the morning saying Momma and the baby both came down with scarlet fever and died two days apart. I got sent back to Skunk Holler, but this time my tears did not stick inside. I cried them out, slept hard and woke up convinced Momma knew I loved her (I still figured the baby for a changeling). Helen Spence saved me from the storm. She showed me that time, like the river, doesn’t flow in a straight line.

Copyright 2016 by Denise White Parkinson